Tanit Haunts Gaius All The Way Back To Rome:

Tanit haunted Gaius on the return trip to Rome. She was never more than a few feet away. She was always at his elbow. She was frequently playing an instrument that resembled a lyre, holding it to her cheek and singing in the Carthaginian language which seemed mysterious to him and which he could not understand. But her lilting melodies haunted him throughout the day and even the night.

Cato was deaf and dumb to such things and went about his business on the deck commanding the ship’s officers and the captain all the way back to Italy.

In the meantime Gaius was afraid that they had taken aboard some pagan goddess, the one named Tanit herself, the Moon Goddess. He was wondering what the Carthaginians had sent to Rome. Could it be more powerful than Hannibal and all his elephants?

When Tanit put away her lyre she was even more remarkable and enchanting. She conversed in both Greek and Latin fluently at the captain’s dinner table aboard the ship. Though a girl, apparently great care had been lavished on her education. She was well-grounded in all the classics and could carry on a Platonic dialogue with great skill.

“In Rome,” Cato growled, “we would never educate a young lady like that.” He stuffed his face with a stew made from octapus and squid. “Who are you anyway?”

Gaius Antonius had been dying to find that out. But he had not had the courage to ask himself.

She smiled radiantly. “I am the only daughter of Hamilcar II, the ruler of Carthage. In fact, I am his only child. He lavished on me all the attention he would have loved to lavish on his heir.” She spoke with astonishing frankness.

“Why were you of all people sent as a hostage to Rome?” Cato shot another question at her. “You would think that someone else would have gone in your place.”

She laughed. Her laugh was like pearls bubbling out of her mouth and popping. “I volunteered,” she explained.

Cato traded looks with Gaius. “And why would you volunteer for such a mission?”

Tanit shrugged in a casual fashion. “Simply because I always wanted to travel to Rome. I didn’t see it happening in any other way. Soon I would be married off. Then I certainly would not get to go.”

“Why would you want to visit Rome so much?” Gaius finally got over being flustered and managed to get the words out of his mouth. He was playing with his food and had a hard time concentrating on eating it.

“Better art, better books,” she said. “For instance, I have heard that you are writing a book on Roman agriculture,” she addressed Cato. “No one has ever done that before. Certainly not in Carthage.”

“The Greek poet Hesoid wrote Works and Days,” Cato informed her.

“Yes, but he was a poet, not a prose writer,” she objected. “You are supposed to be developing Latin prose as you go along.” She acted very well informed about what was happening beyond the borders of her homeland.

But Gaius assumed that Cato’s fame was spread far and wide in the region.

Gaius had never heard a woman discourse like her before, certainly not Lavinia who was quiet and minded her own business.

He was beginning to think that the ship returning to Rome was like a floating enchanted isle controlled by a Circe-like creature. But he wished it would never end.

“Do you think the Carthaginians sent her because she is a kind of ambassador for their city?” Gaius asked Cato on the day before they were to land in Ostia.

“Let’s hope so,” he said cynically. “Let’s hope it is not some trick we cannot yet guess at.”

Gaius was later to remember those all too fateful words. But for now the only alarm he felt was when they started to disembark. Tanit had taken his arm. Lavinia was standing there on the shore waiting for him, smiling at him, and not suspecting anything.

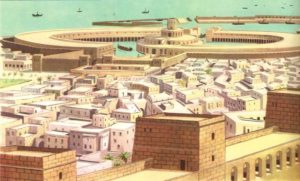

Reconstruction of Carthage by L. Aucler.